Amid a flurry of state-backed media reports heralding the activation of a revolutionary national internet infrastructure, China has projected an image of unmatched technological dominance to the world. This narrative, however, encounters a starkly different reality on the ground, where technical professionals and international businesses grapple with a system that appears far less capable than advertised. A critical examination of the available data and firsthand accounts reveals a profound disconnect between the official hype surrounding this new network and its actual operational performance. While China’s evolution into an industrial and manufacturing titan is an undisputed achievement, the lofty claims about its international internet connectivity warrant deep skepticism, suggesting an infrastructure built not for open global access but for a very different set of strategic priorities.

The Reality Behind the Claims

Questionable Performance and Misleading Metrics

A significant issue with the official narrative is its reliance on performance metrics that appear designed to impress rather than inform, often failing to withstand even basic technical scrutiny. One widely circulated example used to showcase the new infrastructure’s power involved a data transfer of 72 terabytes over a period of 699 days. While the raw numbers seem impressive, a simple calculation reveals an average data transfer rate of approximately 10 megabits per second (Mbps). This bandwidth is notably underwhelming, falling short of the capabilities offered by common VDSL technology found in many residential homes. This massive discrepancy suggests that the official communications may be employing unconventional calculation methods or selectively choosing benchmarks that create a misleadingly favorable impression of the system’s true capabilities, glossing over the practical limitations that would be relevant to any professional user.

This pattern of presenting unverified or context-free data points is a recurring theme in reports from state-affiliated sources, making independent assessment extremely difficult. The lack of standardized testing protocols or third-party validation means that claims of high-speed connectivity cannot be reliably compared against global standards. Such reporting tends to focus on peak theoretical speeds achieved under ideal, controlled conditions, while conspicuously omitting any mention of sustained performance, latency issues, or packet loss—all critical factors in real-world network usability. This selective presentation of information serves to build a narrative of technological supremacy, but it obscures the more complex and often less flattering reality of the infrastructure’s day-to-day operational capacity, particularly when it interacts with the global internet beyond China’s borders.

The Great Firewall’s International Bottleneck

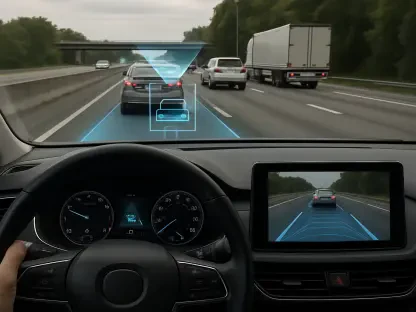

The theoretical prowess claimed by officials stands in stark contrast to the persistent and significant issues reported by professionals who rely on data transfers with Chinese partners. The user experience for international connectivity is frequently plagued by network errors that corrupt or interrupt data flow, often necessitating the cumbersome process of segmenting large files into smaller chunks simply to ensure they can be transmitted successfully. This is not a sporadic issue but a consistent operational hurdle that points to a fundamental bottleneck at China’s international gateways. These problems directly contradict the image of a seamless, high-performance network and suggest an infrastructure that may be heavily optimized for domestic traffic and control at the expense of robust and reliable global integration, creating immense friction for international business and collaboration.

The most striking evidence of this international bottleneck comes from documented cases in major southeastern industrial cities, where upload bandwidth for businesses was observed to be throttled to as low as 50-60 kilobits per second (Kbps). This rate is reminiscent of dial-up internet from decades past and is functionally unusable for modern commercial data exchange. Such severe limitations indicate that poor international performance is not an accidental flaw but a feature of the network’s design. The system appears engineered to prioritize internal data circulation and the enforcement of the state’s extensive content filtering apparatus. Consequently, international traffic is deprioritized, creating a digital chokepoint that insulates the domestic network while severely hampering its utility as a conduit for global commerce and communication, revealing the true priorities behind its architecture.

Acknowledging China’s Industrial Power

From Low-Cost Production to High-Tech Leadership

Skepticism of China’s internet claims should not be conflated with a denial of its genuine and formidable technological and industrial might. The nation has successfully undergone a profound transformation, mirroring the industrial ascent of Japan in the 1980s, to become a global leader in multiple high-tech domains. The outdated Western perception of Chinese industry as being focused on “cheap trinkets” is dangerously misinformed. A prime example of this evolution can be found in the printed circuit board (PCB) sector. Chinese factories are no longer synonymous with low-quality production; instead, many now operate fully robotized production lines equipped with state-of-the-art machinery capable of processing millions of unique orders annually. Their competitive advantage stems not from cheap labor but from massive infrastructure investments that enable economies of scale, allowing them to offer features as standard that are considered premium, costly add-ons elsewhere.

This industrial metamorphosis is reshaping global supply chains and challenging established manufacturing hubs. High-quality components found in premium Western products, including those with a reputation for “German quality,” very often originate in China’s advanced manufacturing facilities. This shift represents more than just an increase in production volume; it reflects a deep commitment to technological advancement, process optimization, and capital investment. The country’s ability to rapidly adopt and scale new manufacturing techniques has created a powerful ecosystem where innovation can be quickly translated from design to mass production. This capability ensures that China is not merely a follower in the global tech race but is increasingly setting the pace in critical areas of hardware production and industrial automation.

Strategic Control of Supply Chains and Infrastructure

China’s technological prowess is further cemented by its strategic vertical integration and unmatched implementation speed. The country’s dominance in the mining and processing of rare earth elements—materials that are essential for virtually all modern electronics, from smartphones to electric vehicles—provides a critical strategic advantage. This control over the foundational level of the supply chain gives it significant leverage and insulates its industries from global supply disruptions. This raw material supremacy is combined with a vast and continuously growing pool of engineering talent and supportive industrial policies, creating a powerful, self-reinforcing ecosystem for rapid technological development and innovation that is difficult for other nations to replicate.

The country’s capacity to execute massive infrastructure projects at a scale and speed that is unparalleled elsewhere is another key pillar of its strength. This is vividly demonstrated by its deployment of 3.4 million 5G base stations, a figure that represents a staggering 60 percent of all global installations. This achievement showcases a formidable ability for national-level implementation, even if the user-facing performance of its public internet has different priorities. This capacity for rapid, large-scale deployment is not limited to telecommunications but extends across various sectors, including high-speed rail and renewable energy. It signals a state-driven ability to mobilize resources and overcome logistical hurdles on a massive scale, a crucial factor in its long-term technological and economic strategy.

Navigating a Controlled Information Landscape

The Challenge of State-Controlled Media

A central difficulty in forming an accurate, objective picture of Chinese technological advancements lies in the nature of its primary information sources. The main outlets reporting on these developments, such as the China Daily, are state-affiliated entities. Their fundamental role is not to practice independent, investigative journalism but rather to advance governmental communication objectives and project a specific, state-sanctioned narrative. This reality necessitates a deeply critical approach to all official announcements and proclaimed breakthroughs. Without the checks and balances of a free press, official reports are free to present a version of reality that aligns with national policy goals, regardless of how closely it corresponds to the facts on the ground. This makes independent verification an essential, albeit challenging, task for anyone seeking to understand the true state of affairs.

This controlled information ecosystem creates a significant barrier for international observers, analysts, and businesses. Reports are often tailored for both domestic and international audiences to project an image of inevitable technological ascendancy and internal stability. The absence of critical questioning or alternative viewpoints within the domestic media landscape means that the official narrative goes largely unchallenged. For those outside the system, this requires piecing together a more accurate picture from a variety of sources, including technical analysis, user testimonials, and observations from businesses operating in the country. This process is painstaking and highlights the fundamental challenge of assessing progress in an environment where transparency is subordinate to narrative control, and information itself is treated as a strategic asset.

Identifying Biased Reporting and Narrative Framing

The reporting on technology that emerges from Chinese state media frequently exhibits several concerning patterns of bias that are designed to shape perception. These include the consistent presentation of unverified performance metrics without any reference to independent testing protocols, the use of selective comparison frameworks that are inherently designed to favor Chinese achievements, and the conspicuous omission of any significant implementation challenges, budget overruns, or deployment limitations. This carefully curated presentation of information creates a distorted reality where every project is an unqualified success and every metric exceeds international benchmarks. This approach is not about conveying technical facts but about constructing a powerful story of national competence and superiority for both domestic and global consumption.

Beyond the manipulation of data, a more subtle but equally important tactic is the framing of infrastructure control mechanisms as purely technical achievements. The sophisticated systems used for content filtering and surveillance, often known collectively as the Great Firewall, are a case in point. In official discourse, these are rarely presented as tools of censorship or social control. Instead, they are framed as innovations in network management, cybersecurity, and the creation of a “healthy” online environment. This reframing illustrates an important distinction: technical capability is conflated with intent. While Western research networks may possess comparable or even superior infrastructure, they are built on a philosophy of open information exchange. In contrast, China’s network is designed to serve a different primary objective: a closed, domestically optimized system that prioritizes control and stability over open access.

A Concluding Perspective

The analysis of China’s new internet infrastructure revealed a system defined by a stark dualism. On one hand, the nation demonstrated its undisputed status as an industrial titan, with world-leading capabilities in manufacturing, supply chain control, and large-scale project deployment that have rendered outdated Western perceptions dangerously obsolete. The industrial power that built the physical components of this network was never in doubt. On the other hand, this industrial might was coupled with an information ecosystem that prioritized narrative control over transparent reality. The operational performance of the country’s international internet links ultimately exposed a system with fundamentally different priorities than those of open, globally integrated networks. The severe bottlenecks and unreliable connectivity were not a failure of technical capability but rather the predictable outcome of a network architecture designed foremost for domestic surveillance and control. This understanding was crucial for navigating a complex landscape where official assertions often diverged from lived experience.