As AI workloads push data center infrastructure to its physical limits, the engineering principles that have guided the industry for decades are being fundamentally rewritten. To navigate this new landscape, we sat down with Matilda Bailey, a leading specialist whose work at the intersection of networking and infrastructure provides a unique perspective on the future of facility design. With rack densities soaring, construction timelines compressing, and power grids straining, her insights reveal a discipline in rapid, high-stakes transformation.

Our conversation explores the tectonic shifts reshaping the industry. We delve into the practical challenges of integrating liquid cooling into legacy systems and managing the immense structural and electrical loads of next-generation hardware. Bailey also sheds light on the move from bespoke projects to the “productization” of data centers, a change driven by a new class of institutional investors. Finally, we discuss how facilities are evolving from passive energy consumers to active grid partners and how AI is creating a new paradigm of operational intelligence through digital twins, all while balancing the competing demands of energy, water, and carbon sustainability.

As liquid cooling shifts from niche trials to standard design, how are your teams standardizing safety and control systems for mixed cooling environments? Can you walk us through a specific challenge you’ve overcome when integrating these new liquid systems with legacy power and monitoring platforms?

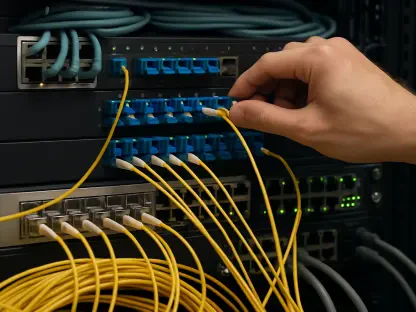

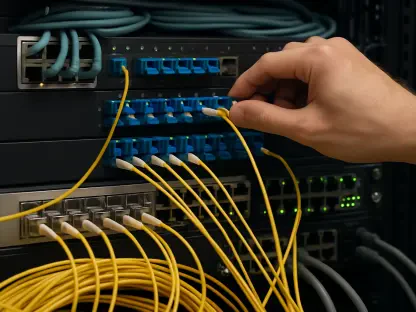

It’s a fascinating transition because we’re moving from a world where liquid cooling was this exotic thing in a lab to something that has to be a reliable, repeatable part of a massive facility. The real work isn’t just in the piping; it’s in the brain—the control systems. We’re focused on creating a unified control architecture, a single pane of glass where an operator can see both their legacy air-cooled halls and the new direct-to-chip systems without having to switch between four different monitors. On a recent project, we faced exactly that challenge. The new liquid cooling skids came with their own sophisticated, IP-enabled controllers, but the facility’s central BMS was a decade-old system built entirely around air handlers and CRAC units. Getting them to talk was a nightmare of mismatched protocols. We had to develop a custom middleware layer to translate the high-frequency data from the liquid pumps into something the old BMS could understand, ensuring that a leak detection alarm in the new system would trigger the same emergency power-off sequence as a fire alarm in the old one.

With design loads now exceeding 100 kW per rack, what specific structural and power distribution changes are becoming common? Please share some metrics on how the commissioning process has evolved to manage the added complexity and smaller margin for error in these high-density environments.

When you hear a client request 100-200 kW per rack, it changes the entire conversation. We’re no longer just talking about IT; we’re talking about fundamental physics. Structurally, the floor loading becomes immense. We’re moving beyond simple raised floors to heavily reinforced concrete slabs, sometimes with dedicated channels cast directly into the floor to handle the weight and volume of coolant piping and busways. Power distribution is also being completely rethought; instead of running whips from a central PDU, we’re seeing more rack-level power distribution and high-voltage busbars running directly to the rows. Commissioning has become exponentially more intense. It used to be a checklist exercise, but now it’s a full-scale, integrated systems test under heavy, simulated load. The margin for error is razor-thin. A single misconfiguration in a cooling pump’s variable speed drive or a fault in a power bus could cause a catastrophic thermal event in seconds, not minutes. So, our commissioning scripts are now incredibly detailed, and we spend far more time validating the dynamic response of the integrated systems rather than just checking if individual components turn on.

The market is shifting from one-off builds to industrial-scale delivery funded by institutional investors. How does this “productization” of power and cooling systems change an engineer’s daily workflow, and what role do digital configuration engines play in meeting demands for compressed schedules and predictability?

It’s a profound shift in mindset, moving from being an artisan to being a manufacturer. A few years ago, my job was to create a unique, bespoke design for a single 12 MW building. Now, that 12 MW building is just one data hall in a multi-hundred-megawatt campus, and my job is to ensure our designs can be replicated perfectly and predictably across the globe. This “productization” means my day is less about drawing lines in CAD and more about defining the parameters for a configurable system. We treat a cooling plant or a power system as a product with a defined SKU. Digital configuration engines are the linchpin of this entire approach. These tools allow us to input a client’s requirements—rack density, PUE target, regional grid codes—and the engine automatically generates a validated, buildable design based on our pre-engineered modules. This is what institutional investors, like pension funds, want to see. They demand predictable cost curves and compressed schedules, and they penalize the risk of a one-off, unproven design.

Given that securing reliable power is a defining constraint, data centers are becoming controllable grid assets. What new technical skills must electrical engineers master to manage this dynamic interaction, and could you provide an anecdote of a project that successfully integrated on-site storage or generation?

The electrical engineer’s world used to end at the facility’s utility demarcation point. Today, that boundary has dissolved. The most critical new skill is a deep understanding of utility transmission and grid dynamics. Engineers now need to design systems that not only draw power reliably but can also interact with the grid, providing services like demand-side response or voltage stability support. They need to be fluent in utility protection schemes and real-time data exchange protocols. We worked on a project recently built on the site of a decommissioned power station. The grid connection was substantial but constrained. We integrated on-site gas turbines, not just for backup, but as a primary power source during peak grid load. The system was designed to seamlessly reduce its grid draw in response to utility signals, effectively acting as a virtual power plant. This dynamic capability was the key factor that unlocked the utility’s approval for a facility of that scale, turning a potential constraint into a strategic asset.

The text mentions that AI is creating live digital twins for performance simulation. Could you detail the key steps for building a meaningful digital twin for a facility? Also, how do you train operators to interpret the AI’s recommendations for optimizing systems like airflow and pump speeds?

Building a meaningful digital twin isn’t about just having a pretty 3D model; it’s about creating a living, breathing replica of your facility’s physiology. The first step is instrumenting everything. We need real-time data from every IP-enabled device—pumps, fans, power meters, temperature sensors. The second step is building the physics-based model that understands how all these components interact. The third, and most critical, step is continuously feeding the live data into that model, so it accurately reflects the facility’s current state. Finally, you layer the AI on top to run simulations—what happens if I lose a cooling unit, or if the outside air temperature rises by five degrees? For operators, the training is all about moving from being reactive to being predictive. We don’t just teach them to follow the AI’s recommendation, like “increase pump speed by 7%.” We train them to query the AI, to understand the data behind the suggestion, and to use the digital twin to validate the expected outcome before they ever touch a real-world control. They become conductors of an orchestra, not just players.

You highlighted the tension between energy efficiency (PUE) and water efficiency (WUE). What design strategies do you use to balance these competing goals at a facility-wide level? Please share an example where a sustainable choice, like heat reuse, led to measurable project success.

This is the central sustainability dilemma we face, especially as densities rise. You can get a fantastic PUE using evaporative cooling, but your water consumption can go through the roof, which is simply not an option in many parts of the world. The strategy is to design for flexibility. We engineer hybrid cooling systems that can operate in different modes—for instance, using direct air-side economization in cooler, drier months and switching to a closed-loop liquid system when it’s hot and humid. This allows us to optimize for either PUE or WUE depending on real-time conditions. We had a huge success on a project in a colder European climate where we implemented a large-scale heat reuse program. The high-density liquid cooling system produced high-grade waste heat. Instead of just venting it, we captured it and piped it to a local district heating network, providing low-cost warmth for a nearby community. This didn’t just improve our sustainability credentials; it became a crucial part of our planning approval and built an incredible amount of goodwill, turning the data center from a perceived energy burden into a recognized community asset.

What is your forecast for the single biggest unforeseen challenge the data center industry will face by 2030, beyond the trends we’ve discussed today?

Looking toward 2030, I believe the biggest unforeseen challenge won’t be a technology problem—it will be a human systems problem. As we industrialize, automate with AI, and integrate these massive facilities into the grid, the complexity is skyrocketing while the margin for error is shrinking to zero. My forecast is that our biggest challenge will be the scarcity of human talent capable of designing, commissioning, and operating these hyper-complex ecosystems. A single data center campus will soon have the grid impact of a small city, run by AI-assisted controls and cooled by intricate liquid systems. The number of people who can truly understand how all those pieces interact, especially during a cascading failure event, is dangerously small. The unforeseen crisis won’t come from a server failing; it will come when we can’t find enough people with the holistic skills to manage the machine we’ve built.