With us today is Matilda Bailey, a networking specialist who has spent her career at the forefront of next-generation infrastructure. Her work provides a unique lens on the foundational pillars that support our digital world, particularly the critical relationship between advanced computing and the energy grids that power it. In light of the recent merger between TMTG and TAE, we’re here to discuss their ambitious plan to power the AI boom with nuclear fusion and what it truly means for the future of data centers.

The TMTG/TAE merger aims to deliver a groundbreaking 50 MWe utility-scale fusion plant. Based on your experience, what are the primary technical and regulatory milestones they must clear to achieve this, and how would that process differ from previous experimental fusion projects?

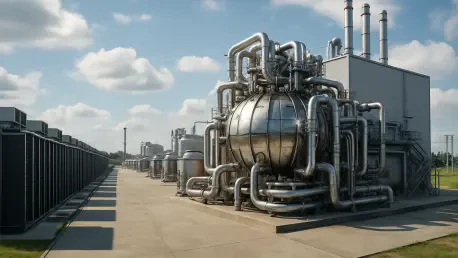

The leap from an experimental reactor to a utility-scale plant is monumental, and it’s where the real challenges begin. For decades, the goal of fusion projects was simply to prove the science—to achieve a net energy gain in a controlled lab setting. Now, with this 50 MWe project, the goalposts have moved dramatically. Technically, they must demonstrate not just a brief burst of power, but sustained, reliable energy generation that can be integrated into the grid. This involves a whole new level of engineering for durability and operational efficiency. On the regulatory side, this is uncharted territory. Previous projects answered to scientific review boards; this one must answer to utility commissions and federal energy regulators who are accustomed to fission, not fusion. They will have to create and navigate a safety and licensing framework that doesn’t even exist yet, which is a process that could easily take years and defines the project’s ultimate success or failure.

Analyst Steven Dickens compared fusion’s 10-15 year timeline to quantum computing. With AI data centers facing a power crunch now, could you outline the specific metrics or breakthroughs we should watch for that would signal this project is accelerating faster than that cautious forecast?

That’s an excellent and very practical question, because the 10-15 year timeline feels agonizingly slow when you see the immediate power demand from AI. To know if they’re beating that clock, we need to look past the press releases and watch for tangible, on-the-ground progress. The first major signal would be securing a location and breaking ground on the actual 50 MWe plant. That moves it from a concept to a concrete construction project. Another key metric is the successful, repeatable demonstration of their core technology outside of a pure research environment, proving it’s ready for commercial application. I’d also be watching for major supply chain and partnership announcements, not with other tech firms, but with established industrial and energy infrastructure players. When you see a major utility sign a firm power purchase agreement or a government agency fast-track a key permit, that’s when you know the momentum is real and the timeline might genuinely be shrinking.

The article notes Trump’s skepticism toward renewables and suggests the merger could be a play for regulatory favor. How might this political alignment specifically impact the project’s pathway through permitting and public funding compared to a project emphasizing sustainability benefits?

The political framing of a project like this is absolutely critical to its trajectory. A project aligned with an administration skeptical of renewables could see a very different path. For example, it might be championed under the banner of national energy security and dominance, which could potentially streamline environmental impact reviews or prioritize it for federal loan guarantees aimed at bolstering the domestic energy supply. You can imagine a scenario where it’s positioned as a strategic asset, allowing it to bypass some of the hurdles a project framed purely around its green credentials might face. Conversely, a project emphasizing sustainability might attract more ESG-focused investment and grassroots public support, but it could also face more intense scrutiny on its environmental promises. The fact that the TAE press release reportedly didn’t even mention sustainability is telling; it suggests they are strategically choosing to navigate the regulatory world as a hard infrastructure and energy independence play, not a climate solution.

The Futurum Group believes fusion’s risk profile is shifting from a “science project” to a commercial opportunity. Can you walk us through the key steps and economic shifts that must occur for investors to see fusion not as a binary bet, but as a bankable infrastructure asset?

That shift from a “science project” to a “bankable asset” is the holy grail for any deep-tech venture. For fusion, the journey has several distinct stages. First, the technology has to be proven reliable and repeatable at a commercial scale, moving beyond one-off successes in a lab. Second, a clear and predictable regulatory pathway must be established. Investors absolutely despise uncertainty, and until there is a clear roadmap for licensing and operating a fusion plant, it remains highly speculative. The third, and most critical, step is demonstrating economic viability. This means proving that the levelized cost of energy from their fusion plant can compete with other forms of baseload power, like advanced fission or natural gas. Once you have those pieces, the final transformation happens when they can secure long-term Power Purchase Agreements from huge energy consumers, like the data center operators building campuses that need hundreds of megawatts. That guaranteed revenue stream is what turns a speculative venture into a stable, predictable infrastructure asset that a bank or a pension fund would feel comfortable financing.

What is your forecast for the role of nuclear fusion in the global energy mix by 2040, specifically considering the projected fivefold increase in data center power consumption?

By 2040, I don’t believe fusion will be a dominant force across the entire global energy grid, but I do think it will have carved out an absolutely critical and strategic niche. Given that data center power consumption is projected to quintuple in that time, we’re going to need specialized, high-density power sources located precisely where those massive AI compute clusters are being built. I forecast that by 2040, we will see the first few utility-scale fusion plants, perhaps like the one TMTG and TAE are proposing, coming online and operating specifically to power these enormous data center campuses. So while the broader grid will still rely on a mix of renewables, fission, and natural gas, fusion will become the dedicated baseload workhorse for the absolute most demanding digital infrastructure. It won’t be everywhere, but where it exists, it will be indispensable.