While most mobile users focus on protecting their devices from malware and phishing scams, a far more fundamental vulnerability persists within the very networks that connect them, hiding in plain sight as a relic of a bygone technological era. Security experts are increasingly highlighting the significant risks posed by second-generation, or 2G, cellular networks, an outdated standard that continues to serve as a backdoor for sophisticated surveillance and data interception. This is not a theoretical threat confined to cybersecurity journals; it is an active and exploitable weakness that can be leveraged by attackers using relatively inexpensive and accessible equipment to undermine the security of even the most modern smartphones. The core of the problem lies in an architectural flaw from the 1990s that modern networks have fixed, yet our devices remain compatible with it, creating a dangerous and often overlooked attack vector.

1. The Technical Flaws That Make 2G a Hacker’s Paradise

The security deficiencies inherent in 2G networks are a well-documented consequence of their decades-old design, primarily stemming from a critical omission in their authentication protocol. Unlike contemporary 4G and 5G networks, which employ robust mutual authentication where both the mobile device and the cell tower must verify each other’s legitimacy, 2G technology operates on a one-way street. It only requires the phone to authenticate itself to the network, meaning the tower’s identity is taken on trust. This fundamental design flaw creates a gaping security hole that malicious actors can exploit by deploying their own fraudulent base stations, commonly known as IMSI catchers or “Stingrays.” Since a smartphone has no mechanism to question the authenticity of a 2G tower, it will readily connect to a fake one that is broadcasting a strong signal. Once this connection is established, the attacker is perfectly positioned to execute a man-in-the-middle attack, giving them the power to intercept, monitor, and potentially alter all incoming and outgoing communications, including voice calls and text messages, in real time without the user’s knowledge.

Compounding the authentication issue is the laughably weak encryption used by the 2G standard, which offers little to no protection by today’s security standards. The primary encryption algorithm employed in GSM networks, known as A5/1, was considered strong at the time of its creation but has long been compromised. Security researchers have repeatedly demonstrated that with minimal computing power, communications encrypted with A5/1 can be decrypted within minutes, rendering the protection it offers effectively useless against a determined attacker. In many network implementations, even weaker versions of the algorithm are used, and in some cases, encryption is not implemented at all, leaving user data completely exposed. This combination of a broken authentication model and obsolete encryption protocols makes the 2G network an insecure environment, transforming any device that connects to it into an open book for anyone with the right tools and intent to eavesdrop.

2. Real-World Exploitation and Government Surveillance

The vulnerabilities of 2G are not merely academic concerns; they are actively and widely exploited in the real world by a diverse range of actors. Law enforcement and intelligence agencies across the globe have notoriously used IMSI catchers for years to conduct surveillance operations, tracking suspects’ locations and intercepting their communications without needing a warrant from a service provider. However, the technology required to create a fake 2G base station is no longer the exclusive domain of government entities. The proliferation of affordable software-defined radio (SDR) hardware and open-source software has democratized this powerful surveillance capability. Today, criminal organizations, corporate spies, and even individual stalkers can acquire or build their own IMSI catchers for a few thousand dollars, dramatically expanding the threat landscape. This accessibility means that anyone with a motive could potentially target an individual, a company, or a group of people at a public event like a protest or a conference.

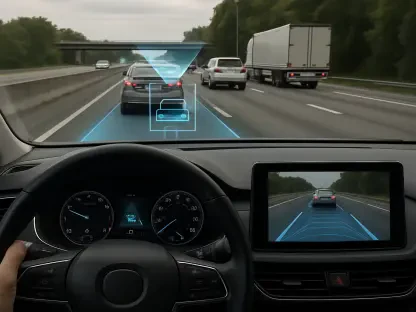

The tangible impact of these attacks has been documented in numerous incidents affecting journalists, political activists, and business executives. In many cases, attackers exploit the “fallback” mechanism in modern smartphones. By using a jammer to block stronger 4G and 5G signals in a targeted area, they can force nearby phones to downgrade their connection to the insecure 2G network, where the interception can occur. This technique is alarmingly effective and difficult for the average user to detect. While the problem is most severe in regions where 2G is still a primary mode of connectivity, it remains a potent threat even in countries with extensive 5G coverage. As long as a smartphone has 2G capability enabled, it remains susceptible to a downgrade attack, making it a persistent vulnerability that transcends geographic and technological boundaries.

3. The Industry Response and Carrier Shutdowns

In response to the growing awareness of these security risks, telecommunications carriers, particularly in developed nations, have started the process of decommissioning their aging 2G infrastructure. In the United States, this transition is already well underway. AT&T led the charge by completing its 2G network sunset back in 2017, and T-Mobile officially shut down its legacy 2G GSM network in 2020. These moves were driven by a combination of security concerns and the economic incentive to reallocate valuable wireless spectrum to more efficient and profitable 4G and 5G services. By phasing out these outdated networks, carriers not only enhance the security of their customers but also free up resources to improve the performance and capacity of modern networks. However, this progress is not uniform across the globe, as many carriers in developing markets and even some in Europe continue to operate 2G networks to support a large base of legacy devices.

The global transition away from 2G is hindered by significant practical and economic challenges. Millions of devices still in operation rely exclusively on 2G for connectivity, ranging from older feature phones to a vast ecosystem of Internet of Things (IoT) devices, such as smart meters, vehicle telematics systems, and emergency call boxes. For the companies and individuals who own this equipment, the cost of upgrading or replacing the entire installed base represents a substantial financial barrier to a complete shutdown. Furthermore, in many rural and remote areas worldwide, the expansive reach of 2G infrastructure provides the only available cellular signal. In these regions, shutting down the 2G network would mean cutting off essential voice and text services, creating a difficult trade-off for policymakers and carriers who must balance the need for enhanced security against the imperative of maintaining basic connectivity for underserved populations.

4. How to Disable 2G on Modern Smartphones

For individuals looking to proactively protect themselves from 2G-related threats, the most effective step is to disable this outdated connectivity on their smartphones. The procedure differs between operating systems, but most modern devices offer a way to control which network generations the phone is allowed to use. For Android users, this setting is typically found within the mobile network preferences. The exact path can vary depending on the device manufacturer and the version of Android, but it generally involves opening the Settings app, navigating to a section labeled “Network & Internet” or “Connections,” and then selecting “Mobile Network.” Inside this menu, there should be an option for “Preferred network type” or “Network mode.” By selecting an option that exclusively includes modern networks, such as “5G/LTE/4G” or “LTE/3G,” users can prevent their phone from ever connecting to a vulnerable 2G tower. This simple configuration change effectively closes the door on downgrade attacks.

On Apple’s iOS, the ability to manage network preferences has historically been more limited, in line with the company’s philosophy of simplifying the user experience. However, recognizing the security implications of 2G, Apple has introduced more granular controls in recent versions of iOS, although the availability of this feature can depend on the specific iPhone model and the carrier’s settings. To check for this option, iPhone users should go to the Settings app and tap on “Cellular.” From there, under “Cellular Data Options,” an option may be present to either disable 2G directly or to limit connectivity to LTE and 5G networks only. By toggling this setting, users can instruct their device to ignore 2G signals for normal operations. It is a crucial step that empowers users to take control of their device’s security posture and mitigate a significant and preventable risk without relying on their carrier to phase out the network entirely.

5. The Broader Implications for Security

Disabling 2G connectivity on a personal device is a prudent security measure, but it is not a decision entirely without potential drawbacks that users should consider. The primary trade-off is a potential reduction in network coverage, particularly in rural or remote areas where 4G and 5G infrastructure may be sparse or nonexistent. For international travelers visiting countries with less developed telecommunications networks, disabling 2G could mean losing connectivity entirely in certain locations. In these situations, users must weigh the heightened security benefits against the practical need for a reliable connection. However, for the majority of users who live and work in developed markets with comprehensive LTE and 5G coverage, the likelihood of encountering a 2G-only zone is extremely low, making the security advantages of disabling it far outweigh the minimal risk of a coverage gap.

A common concern revolves around the reliability of emergency services, as some jurisdictions may still leverage 2G networks for their expansive reach to ensure emergency calls can be placed from anywhere. Fortunately, smartphone manufacturers and network standards bodies have already accounted for this scenario. Modern devices are engineered with a fail-safe that allows them to temporarily enable all available network technologies, including 2G, when an emergency call (such as to 911) is initiated. This function operates independently of the user’s day-to-day network preferences. Consequently, even if you have disabled 2G for normal use to protect your privacy and data, your phone will still be able to connect to a 2G signal if it is the only one available during a critical emergency, ensuring that this essential safety feature remains fully functional while your routine communications are secured against interception.

6. A Proactive Stance on Mobile Defense

The continued existence of 2G compatibility on modern smartphones represented a significant, albeit addressable, security flaw. By taking a few moments to navigate their device settings and disable this outdated network standard, users could effectively shield themselves from a class of sophisticated interception attacks that relied on forcing a downgrade to the insecure network. For most individuals residing in areas with robust modern network infrastructure, the security gains achieved through this simple action far surpassed any potential inconvenience related to connectivity. The issue underscored a broader principle in the evolving landscape of cybersecurity: as technology became more integrated into daily life, individuals needed to adopt a proactive role in managing their digital defenses rather than passively relying on default configurations that often prioritized compatibility over security. The decision to disable 2G was a clear, impactful step in this direction, reflecting a shift toward greater user empowerment and responsibility in safeguarding personal information.