A fast way to know if your system is truly in sync

Every tap that sends a message, every satellite fix that pins a location, and every clock edge that launches a CPU instruction rides on an invisible promise that two signals will agree not just roughly but precisely, in frequency and in timing, for as long as the job demands. In wireless links, that agreement is fragile: a few tens of picoseconds of wander can shrink a data eye, misplace a symbol, or detune a local oscillator from its channel. Yet those slips rarely make headlines, because phase-locked loops quietly hold the line.

Consider the shared choreography of a 5G handset, a GPS receiver, and a processor core. Each depends on a clean reference and a tuned oscillator that does not just approximate a tone but locks to it, so bits land in the right buckets and carriers line up for mixing. Lose that lock and the consequences cascade: call quality falters, coordinates jump, frames miss their windows. The mechanism that prevents it is not flashy—just tight negative feedback and careful noise shaping—but it decides whether a system hums or stutters.

Tiny timing errors carry outsized cost. A 50 ps peak-to-peak jitter increase can push a 10 Gb/s serial link over its bit-error threshold, while a 1 kHz offset in a narrowband RF path can shrink a coherent integration gain by several decibels. The drift begins small, propelled by temperature, supply ripple, or aging, and ends in dropped packets or lost frames. The fastest way to know if a system is truly in sync is simple: inspect its phase lock—and how rigorously it is kept.

Why phase lock matters now

At heart, a phase-locked loop aligns an oscillator’s frequency and phase to a reference through feedback, minimizing phase error until both signals march together. That lock state is not a moment but a condition: the loop constantly senses phase difference, filters it, and nudges the oscillator so drift never gets a foothold. In the process, it copies the reference’s long-term stability while curating its short-term cleanliness.

Phase and frequency often get mixed in conversation, yet their roles diverge in loop behavior. Frequency offsets show up as a steadily rotating phase error; a PLL first pulls frequency into line, then trims phase to a fixed offset that the loop can hold. That two-step dance explains how loops capture a wandering oscillator, and why loop dynamics—gain, bandwidth, and damping—decide whether capture is brisk and stable or nervous and noisy.

Real hardware is unruly. Reference noise, supply hiss, substrate coupling, and brief interruptions try to shake the output. Good loops tame these insults by choosing bandwidth wisely: wide enough to track slow reference wander and reacquire quickly, narrow enough to keep VCO phase noise from leaking out. Moreover, most loops now live on chips rather than on benches. Integration delivers smaller footprints, tighter matching, and digitally assisted calibration that squeezes better performance from ordinary passives and modest power.

The PLL, unpacked: structure, dynamics, and performance

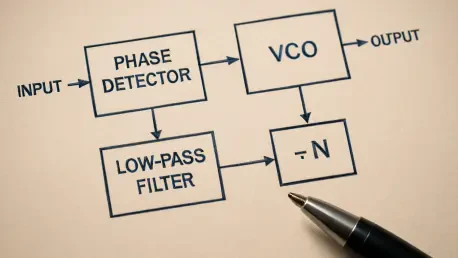

Strip a PLL to its essentials and three blocks remain: a phase detector, a loop filter, and a voltage-controlled oscillator. The detector compares input and feedback phases, converting difference into an error signal. The filter shapes that error into a smooth control voltage, deciding how aggressively the loop responds. The VCO turns that control into frequency change, closing the feedback path. However simple the diagram looks, the choices inside each block set noise, lock time, and resilience.

Lock unfolds in stages. Far from the target, the loop acts like a frequency hunter, using a phase-frequency detector to find the right neighborhood. As the gap narrows, phase takes over, and the loop eases into alignment without overshoot if damping is right. The control-voltage trace tells the story: a glide toward a plateau, small ripples that reveal bandwidth, and a quiet floor when lock holds.

Control theory offers the vocabulary. Negative feedback governs stability, loop gain sets authority, and phase margin keeps oscillation at bay. Capture range defines how far the loop can pull in from a cold start; lock range marks how far it can track once settled. Designers juggle these with a simple truth in mind: faster lock typically means wider bandwidth, which often means more jitter—unless the reference and VCO noise profiles argue for a different split.

Precision hinges on noise. Phase noise describes random phase wander in the frequency domain; time-domain jitter captures the same behavior in picoseconds. These metrics dominate specs because they reveal how a loop spreads energy and blurs edges. A related nuisance is the reference spur: residual tones at multiples of the comparison frequency that sneak through the filter. Tuning loop bandwidth, using clean supplies, and managing charge pump leakage reduce these spurs without sacrificing reacquisition speed.

Modern synthesizers multiply a clean reference into many outputs with counters and dividers. Integer-N designs keep the output as an integer ratio of the reference, yielding low spurs but limited frequency resolution. Fractional-N adds a fractional average with digital modulators, unlocking fine steps at the cost of potential quantization noise and fractional spurs. The payoff is large: one crystal can feed a radio that needs dozens of local oscillators, all phase aligned and channel-accurate.

Across applications, the loop’s utility keeps expanding. In wireless front-ends—from Wi‑Fi to cellular to satellite—PLLs generate low-noise local oscillators that survive crowded spectra. In demodulation, loops track FM and PM directly, enabling coherent detection that boosts sensitivity. In compute, they multiply and clean clocks for CPUs, DRAM, and multi-gigabit SerDes, where sub-100 fs rms jitter can decide throughput. And in burst systems, fast reacquisition turns gaps and fades into brief footnotes, not session resets.

Voices from the field: evidence and experience

Practitioners speak in crisp maxims because field failures punish ambiguity. “Phase lock gives you frequency for free; the hard part is low jitter,” is a line heard across RF labs, a reminder that meeting a channel spec is not victory unless the noise floor is quiet. Another common refrain praises digital phase-frequency detectors for their wide capture ranges and unflappable behavior under large offsets; when a loop must pull in quickly, the PFD earns its place.

Implementation choices reflect scale and need. Communication gear overwhelmingly uses integrated PLLs, bundling PFDs, charge pumps, loop filters, and VCOs with serial control and calibrated trims. Discrete loops still matter at microwave edges or when bespoke filters must shape unusually sharp masks. Hybrid designs split the difference: analog control for low noise, digital calibration for repeatability and fast bring-up.

Snapshots from the field put numbers to claims. A burst radio that shortened lock time from 800 µs to 120 µs cut link setup latency by more than 6×, lifting throughput under duty-cycled traffic. A SerDes backplane that swapped a noisy LDO for a low-impedance supply and narrowed loop bandwidth reduced integrated jitter by 35%, opening the eye diagram at 25 Gb/s. Those wins did not come from novelty; they came from disciplined loop design and validation.

Apply it: design steps, checks, and practical tactics

A reliable workflow starts with a clean statement of need: reference frequency, target outputs, and resolution. Choose integer-N if spur floors and simplicity dominate; pick fractional-N for fine steps or many bands. Next, set loop bandwidth and phase margin to match noise profiles: push bandwidth high if reference is cleaner than VCO near offset, or pull it low if the VCO dominates. Estimate lock time from natural frequency and damping, then verify capture and lock ranges against worst-case offsets and temperatures.

Bring-up favors curiosity and a scope. First, confirm reference integrity at the PLL pin—amplitude, waveform, and spectral purity. Then watch the control voltage during startup; a smooth approach with minimal ringing signals healthy damping. Lock-detect lines help, but trust measurements: sweep temperature and supply to see if lock drifts, and measure phase noise and spurs with the same settings planned for production. Numbers beat intuition when margins are thin.

Troubleshooting becomes faster when symptoms map to causes. Slow or no lock points to low loop gain, bad divider ratios, or a sick reference. Excess jitter hints at an overly wide bandwidth, a noisy supply rail, or a VCO that is too sensitive in the chosen range. Spurs often trace to fractional quantizer patterns, charge pump mismatch, or careless filtering. A short checklist—validate math, isolate supplies, tune bandwidth—often turns a mystery into a fix.

Picking the right IC decides how many of those fights show up. Key selectors include tuning range, phase noise at relevant offsets, availability of an integrated VCO, power draw, and control interface. Going discrete still makes sense at extreme frequencies, in radiation-hardened settings, or when a custom loop filter is central to a spec. Otherwise, modern synthesizers offer dense features and calibration that get to performance faster.

Integration details turn good designs into great ones. Isolate the reference path with clean routing and tight return currents. Decouple the VCO with low-ESR capacitors and keep the loop filter away from digital edges. Separate analog and digital grounds where the silicon vendor recommends, and manage crosstalk and EMI with shielding and layer discipline. Small layout choices move noise by decibels; that margin often decides compliance.

The last word

The road from shaky lock to rock-solid timing ran through feedback discipline, measured trade-offs, and clean implementation. Teams that treated phase noise, spurs, and lock time as a shared budget delivered radios that acquired faster, links that jittered less, and clocks that multiplied without drama. The next steps were clear: quantify noise on both sides of the loop, select architectures that fit resolution and spur limits, and invest in layout hygiene as though it were a gain stage. With that posture, phase-locked loops stopped being mysterious black boxes and became dependable instruments, tuned to the tempo of modern systems.